Feb 1981

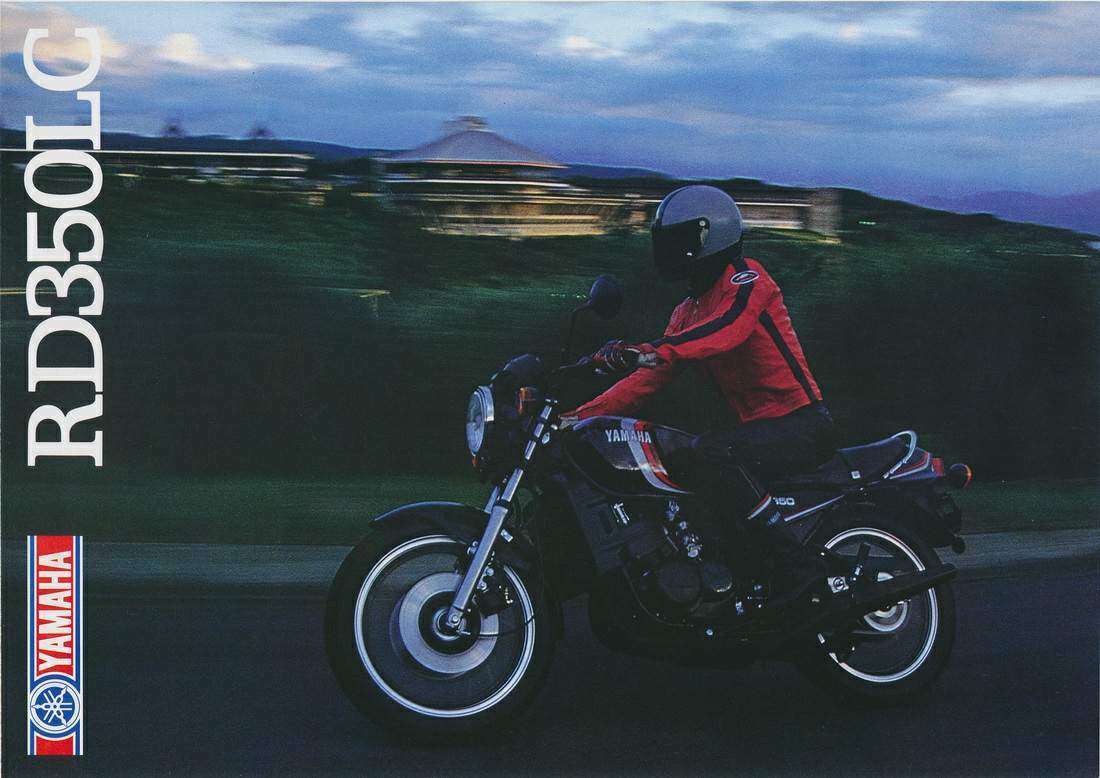

Taking things all round, and allowing for its failings, the RD350LC is still, quite simply, one of the nicest bikes I have ridden. We weren't expecting any great surprises in straight-line performance — even Yamaha were only claiming roughly the same power as the RD400; but plenty of people apparently were looking for big things from the new twin.

It's easy to gauge a bike's popularity by the number of people lining up to scrounge a ride on the road test machine. In this case, not only was the queue longer, but some of them were even prepared to trade things in return for a go on the 350 . . .

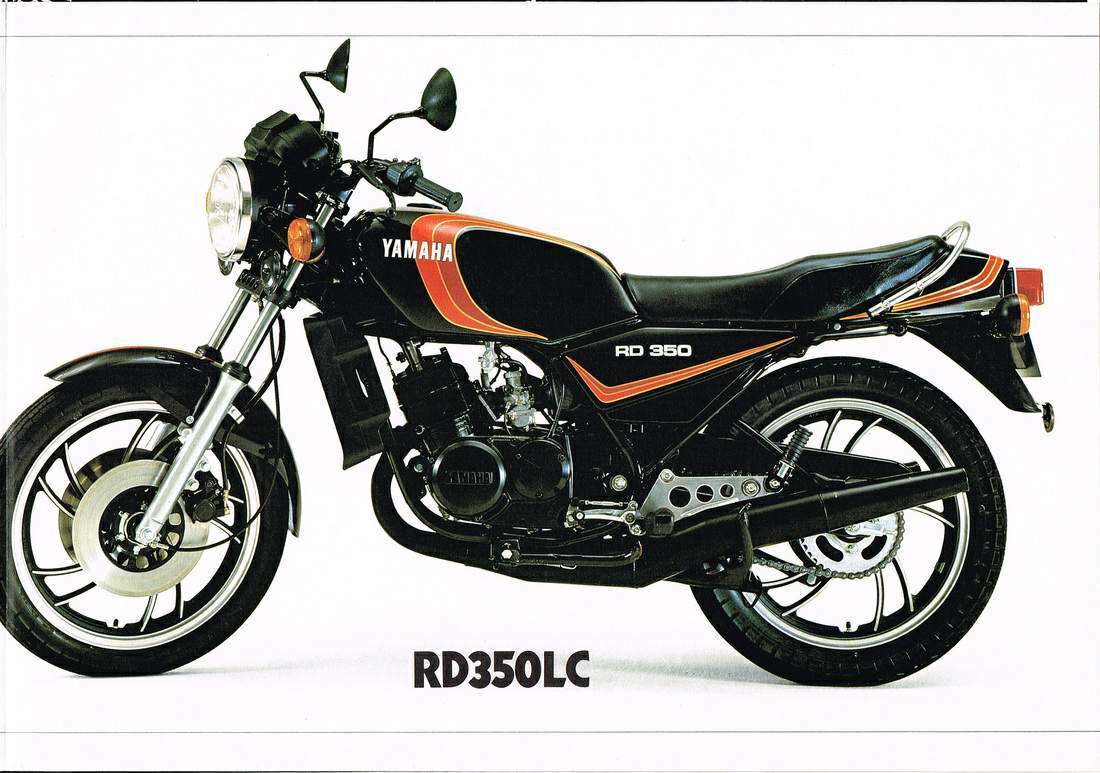

It has a bit more peak power than the 400, and with a best top speed of 113.8, we made it go a few mph faster than our last road-test 400. The basic power characteristics are the same, but the power development is something of an engineering con-trick.

Everyone who rode it came back saying how powerful it was. Yet nobody would try to claim that 42 bhp is "a lot". What they were feeling was the lack of power — at 6,000 it gives 8 bhp less than the RD400 and it does all its catching up between 6,000 and 6,500. On the road, in the lower gears, it is like pulling a trigger. The torque "curve" isn't curved at all. It is bent, with a near-vertical step at 6,500.

This sudden rush of torque gives a wheelie-pulling surge that feels like a lot of power; the power itself isn't great, but the rate of change of power is enormous.

The engineering trick is in making it rideable. They've got all the characteristics of a race engine without any of the splutter and stutter. The RD will actually pull full throttle in top gear from something in the region of 2,000 rpm — admittedly it only pulls about as hard as the average moped but it doesn't miss or gas up.

It could be that they've tuned the motor for peak power and have then had to work hard to get any flexibility at all — which could be one reason for using the small carbs, which are the same as those on the 250. Or it could be that the power characteristics have been deliberately made violent in order to convince the rider that he's getting more than the Yamaha is giving.

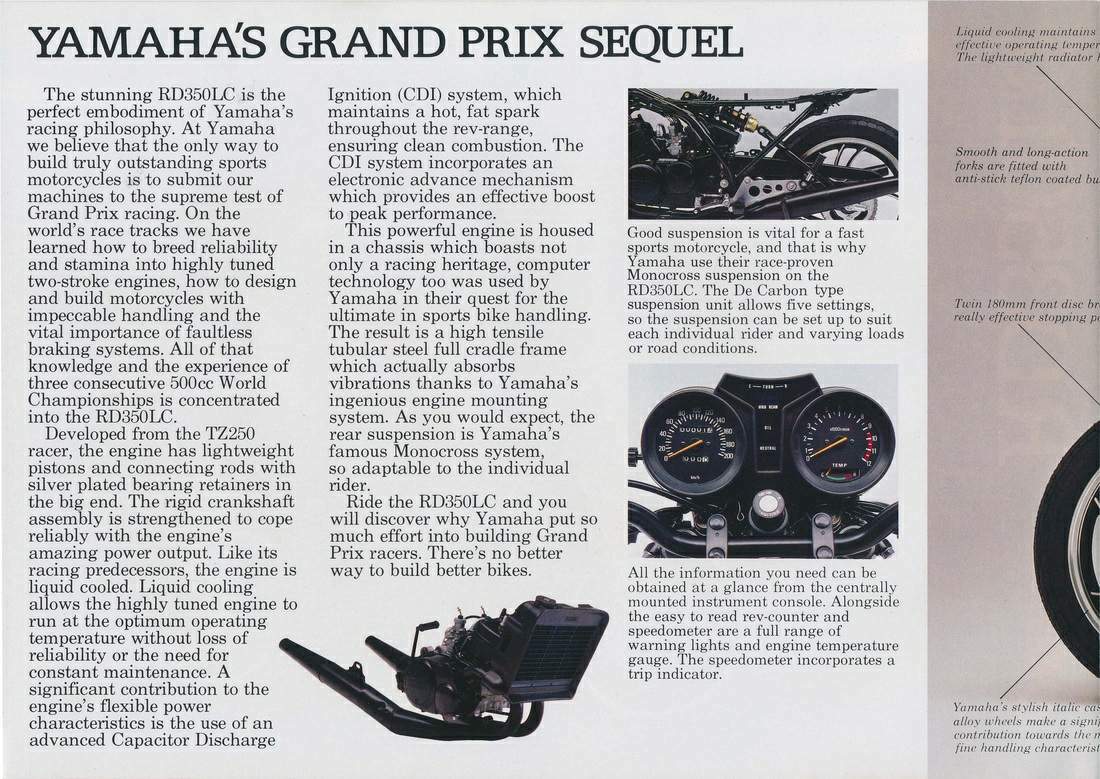

On the road or the track, the liquid-cooled motor runs very cold — around 40 deg celcius according to the temperature gauge. It is tempting to assume that it is over-cooled and that a thermostat would be a good thing. Most cars run at about 85 deg C and the hotter an engine gets, the higher its thermal efficiency — the more power you receive from a given amount of fuel. We ran the Yamaha up to 100 deg C, still in the safe zone on its gauge, and it promptly lost 10 per cent of its power. So its quite obviously isn't over-cooled.

The 180-degree twin is particularly smooth at high speeds, and all through the rev range it feels completely isolated from the frame, footrests, handlebars and mirrors. The only noticeable vibration is at tick-over, when it moves in a lumpy sort of way which increases the rider's impressions of a powerful unit. It was reminiscent of those big V-8 drag cars which shudder and shake their whole bodies every time the throttle is blipped. And to get a little two-stroke to feel like that is quite something!

The only time the bike was difficult was on the rare occasions that I wanted to cruise along at 50 mph against a strong wind. While the 350 would easily hold anything from 60-odd up to 90 mph without needing a lot more than half-throttle, it didn't have the low-speed effort to go slowly. To hold a steady 50 mph into the wind it was usually necessary to change down into fifth or even fourth.

Top speed was some 5 mph up on the RD400 we tested, but the standing quarter was marginally worse, at 13.8 seconds compared to 13.7 for the 400. Perhaps the 350 has the potential to do better but it was spoiled by the bike's propensity for pulling wheelies. With the rider crouched over the bars the 350 would rear up as soon as the tyre or the clutch bit, coming up so fast that the fuel tank would thump the rider's chest.

The exhaust smokes a lot at idle and the engine gets through a fair quantity of oil — usually covering less than 200 miles per pint. Fuel disappeared at an equally alarming rate, with consumption ranging from the mid-20s to a norm of 38 to 40 mpg. Keeping speeds below 50 mph, we achieved 51.2 mpg and it is doubtful whether the twin would do much better than that.

It's worth noting that the TZ Yamahas have detonation problems which reduce the life of their pistons — Yamaha specify premium fuel for the RD, which is quite a rarity in any Japanese engine, let alone a two-stroke.

While the engine has a decent level of power and provides, shall we say, entertaining performance, the best parts of the Yamaha start with the detail design and go through to the complete, integral assembly.